Sedentary Shock: How Excessive Sitting Accelerates Your Biological Clock

- Marcus Reed

- Health , Longevity , Lifestyle , Wellness

- May 3, 2025

Table of Contents

Fast Facts: Sitting & Faster Aging (TL;DR)

- The Hidden Culprit: Prolonged sitting accelerates biological aging independently of your exercise routine.

- Cellular Damage: Excessive sitting is linked to faster telomere shortening, DNA damage, and negative epigenetic changes.

- METs Matter: Sedentary behavior is any waking activity using ≤1.5 Metabolic Equivalents (METs).

- Exercise Isn’t a Full Shield: While vital, exercise doesn’t completely negate the harms of over 6-8 hours of daily sitting.

- Move More, Sit Less, Live Better: Regularly breaking up sitting time is crucial for cellular health and longevity.

- Aim Higher if You Sit More: If you sit for 6-8+ hours daily, you likely need more than the minimum recommended 21 MET-hours/week of activity.

Sedentary Shock: How Excessive Sitting Accelerates Your Biological Clock (Even if You’re Active)

In our hyper-connected, office-centric world, many of us diligently carve out time for exercise, believing this is the ultimate shield against the demands of desk-bound jobs and screen-filled evenings. However, a growing body of evidence-based research unveils a stark and often overlooked truth: prolonged sitting is an independent saboteur of health, capable of accelerating biological aging at the cellular level. This insidious effect can persist even if you meet or exceed daily physical activity recommendations. Understanding this crucial distinction between general physical activity and sedentary behavior is paramount for anyone serious about fostering genuine health, vitality, and longevity. Let’s delve into the science illuminating the health risks of sitting and explore practical, science-backed strategies to counteract this modern-day challenge to our genetic aging.

The Unsettling Truth: Why Your Workout Doesn’t Fully Erase a Day of Sitting

One of the most compelling, and perhaps concerning, findings in recent aging research is that dedicated exercise, while undeniably beneficial for myriad health outcomes, doesn’t grant a free pass from the detrimental effects of excessive sedentary time. Landmark studies indicate that clocking more than 6-8 hours of sitting per day is significantly associated with markers of accelerated biological aging [1], irrespective of whether individuals engage in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Consider sedentary behavior not merely as the absence of exercise, but as a distinct physiological state with its own set of risks that demand specific, targeted interventions beyond just your scheduled gym session or run. Minimizing overall sitting time and breaking up long sedentary stretches are non-negotiable components of a truly anti-aging lifestyle.

Cellular Sabotage: How a Sedentary Lifestyle Rewrites Your Aging Code

The troubling link between too much sitting and a sped-up aging process isn’t just an epidemiological observation; scientists are increasingly pinpointing the specific cellular aging pathways that bear the brunt of our inactivity:

- Telomere Attrition: Telomeres are the protective nucleotide sequences at the ends of our chromosomes, often likened to the plastic tips on shoelaces that prevent fraying. They naturally shorten with each cell division, and critically short telomeres trigger cellular senescence (aging) or apoptosis (cell death). A sedentary lifestyle has been robustly linked to accelerated telomere shortening([11]), effectively making your cells biologically older than your chronological age.

- Compromised DNA Integrity and Repair: Our DNA is under constant assault from metabolic byproducts and environmental factors, leading to thousands of lesions per cell per day. Thankfully, our bodies possess sophisticated DNA repair mechanisms. Physical activity is known to bolster these repair systems. Conversely, prolonged inactivity may lead to sluggish or impaired DNA repair processes, allowing damage to accumulate. This buildup of unrectified DNA damage is a cornerstone of genetic aging and contributes to cellular dysfunction.

- Detrimental Epigenetic Alterations: Epigenetics refers to modifications to DNA that regulate gene activity (turning genes on or off) without changing the underlying DNA sequence itself. Lifestyle factors, critically including physical inactivity, can induce harmful epigenetic shifts. These changes can adversely affect the expression of genes involved in inflammation, metabolic health, stress resistance, and longevity, nudging cells towards an aged, pro-inflammatory state.

- Impaired Stem Cell Function: Adult stem cells are crucial for tissue regeneration, repair, and maintenance throughout life. Chronic inactivity and a sedentary lifestyle can negatively influence the health and regenerative capacity of these vital cells. This may manifest as a depletion of stem cell pools or a diminished ability of remaining stem cells to respond to repair signals, thereby hindering the body’s ability to maintain tissue integrity and contributing to age-related functional decline.

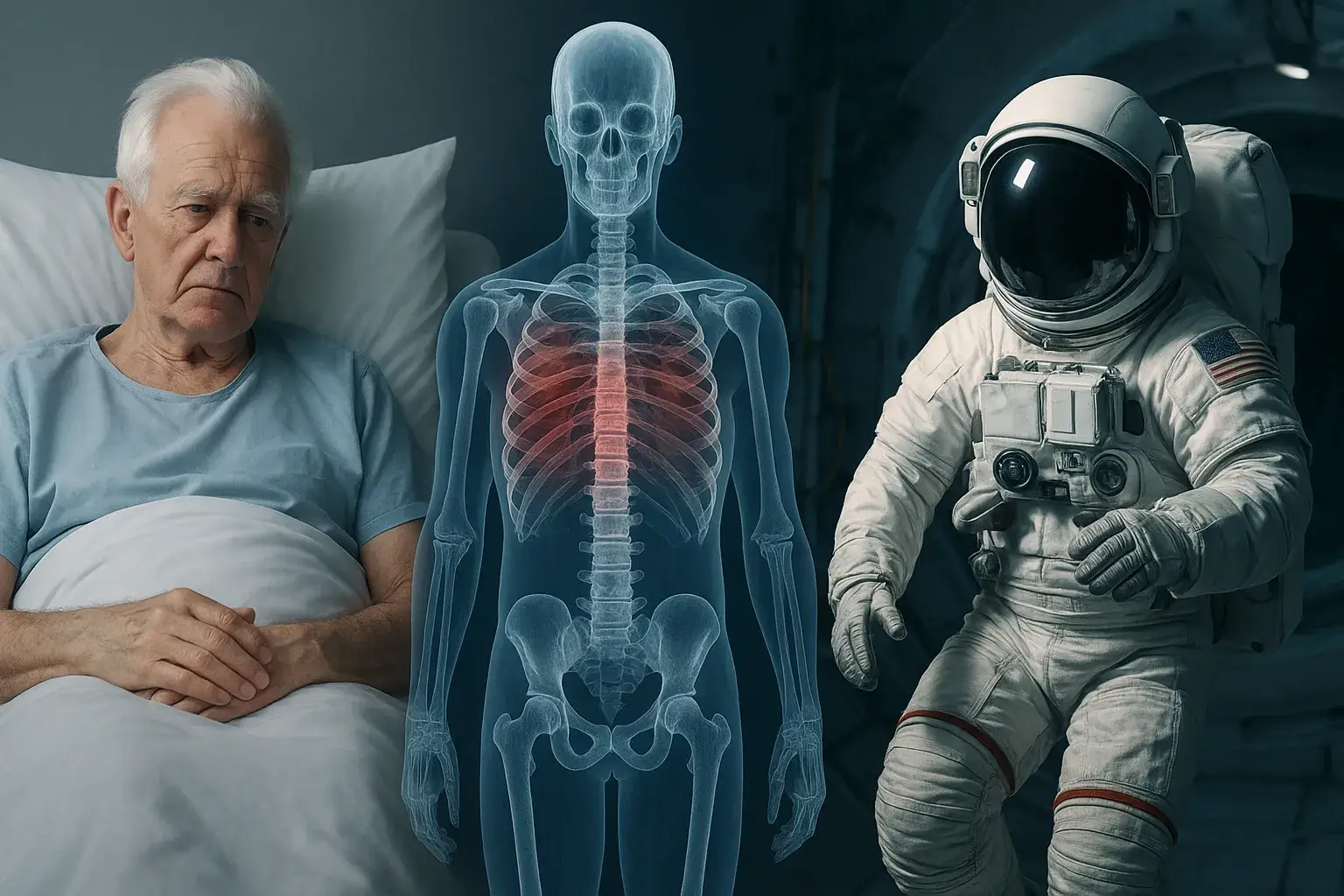

Stark Lessons from Extreme Inactivity: Bed Rest, Spaceflight, and the Fast-Track to Aging

The profound impact of inactivity on aging is dramatically illustrated by studies involving prolonged bed rest([2]) and simulated spaceflight conditions. These scenarios, which enforce extreme sedentarism and unload the musculoskeletal system, induce a rapid cascade of physiological changes that strikingly mimic aspects of natural aging. These include significant muscle atrophy (sarcopenia), loss of bone mineral density (osteoporosis), insulin resistance, and declines in cardiovascular function. Such studies powerfully demonstrate how the absence of regular mechanical loading and movement signals the body to downshift its maintenance and repair programs, thereby accelerating the aging phenotype.

The profound impact of inactivity on aging is dramatically illustrated by studies involving prolonged bed rest([2]) and simulated spaceflight conditions. These scenarios, which enforce extreme sedentarism and unload the musculoskeletal system, induce a rapid cascade of physiological changes that strikingly mimic aspects of natural aging. These include significant muscle atrophy (sarcopenia), loss of bone mineral density (osteoporosis), insulin resistance, and declines in cardiovascular function. Such studies powerfully demonstrate how the absence of regular mechanical loading and movement signals the body to downshift its maintenance and repair programs, thereby accelerating the aging phenotype.

Defining Sedentary: Understanding METs (Metabolic Equivalents)

To objectively quantify activity levels, scientists employ a unit called METs (Metabolic Equivalents of Task). One MET represents the energy expenditure of sitting quietly at rest.

- 1 MET: The energy your body uses when completely at rest, like sitting quietly or lying down.

- Sedentary Behavior: Crucially, any waking activity that expends ≤1.5 METs while in a sitting, reclining, or lying posture is classified as sedentary. This includes activities like watching television, working at a computer, or driving.

- Light Intensity Activity: Activities using 1.6-2.9 METs, such as slow walking, standing, or light household chores.

- Moderate Intensity Activity: Activities using 3.0-5.9 METs, like brisk walking, cycling at a moderate pace, or gardening.

- Vigorous Intensity Activity: Activities using ≥6.0 METs, such as running, swimming laps, or strenuous sports.

You can find detailed MET values for a vast array of activities in the Compendium of Physical Activities([3]). This framework underscores that simply being seated, regardless of how “good” your posture might be, is metabolically a state of very low energy expenditure.

Can Your Workout Outrun a Day of Sitting? The Primacy of All-Day Movement

While high volumes of exercise – for instance, 60–75 minutes of moderate-intensity activity daily – can partially mitigate some of the increased mortality risk([4]) associated with prolonged sitting time (especially if sitting exceeds 8 hours/day), it’s critical to understand that it doesn’t completely erase all the negative cellular and metabolic consequences.

The paramount strategy emerging from evidence-based research is the necessity of incorporating regular movement throughout the entire day. Breaking up extended periods of sitting([5]) with even brief, 2-5 minute bouts of standing, light walking, or simple bodyweight movements appears to be vital for counteracting the detrimental metabolic shifts and cellular stress induced by uninterrupted sedentarism.

Gauge Your Activity: Calculating Your Daily and Weekly MET-Hours

To get a clearer picture of your overall energy expenditure from physical activities, you can use the concept of MET-hours. This metric helps quantify your total activity volume.

The Simple Calculation: MET value of an activity × Duration of the activity in hours = MET-hours

Illustrative Example:

- You engage in 1 hour of brisk walking (approximately 4.0 METs):

4.0 METs × 1 hour = 4.0 MET-hours - You spend 30 minutes (0.5 hours) doing moderate gardening (approximately 3.8 METs):

3.8 METs × 0.5 hours = 1.9 MET-hours - Your Active Total for these activities:

4.0 + 1.9 = 5.9 MET-hours

Setting Your Activity Target: Minimum MET-Hours for Tangible Health Benefits

What’s a reasonable goal to aim for? [Research from sources like the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans and the WHO]([6], [7], [9]) consistently indicates that accumulating more than 21 MET-hours per week (which averages out to approximately 3 MET-hours per day) serves as a minimum threshold associated with a significantly lower risk of all-cause mortality and various chronic diseases.

A Critical Caveat: If your daily sedentary time consistently exceeds 6–8 hours, health experts strongly advise aiming for a considerably higher weekly MET-hour target. This increased activity volume is necessary to more effectively counteract the pervasive negative impacts of prolonged inactivity and substantially reduce the health risks of sitting.

Integrating Movement: Practical, Science-Backed Strategies to Combat Sedentary Aging

The key to mitigating the aging effects of sitting isn’t just about intense workouts; it’s about weaving consistent movement into the fabric of your day. Here are actionable, evidence-based tips:

The key to mitigating the aging effects of sitting isn’t just about intense workouts; it’s about weaving consistent movement into the fabric of your day. Here are actionable, evidence-based tips:

- Strategic Movement Breaks: Employ timers or apps (like a Pomodoro timer) as reminders to stand up, stretch, or take a short walk for 2-5 minutes every 30-60 minutes. This interrupts the harmful continuum of sedentarism.

- Amplify Incidental Activity (NEAT - Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis):

- Consistently choose stairs over elevators or escalators.

- Park further from your destination to add extra steps.

- Pace or stand during phone calls.

- Walk over to a colleague’s desk instead of sending an email.

- Ergonomic and Active Workspace Solutions:

- Consider investing in a standing desk or a desk converter to alternate between sitting and standing.

- Explore options like under-desk ellipticals or treadmill desks for low-intensity movement while working.

- Reclaim Leisure Time Actively: Consciously swap some passive screen time (TV, social media scrolling) for active pursuits like walks in nature, gardening, dancing, playing with pets or children, or engaging in active hobbies.

- Monitor and Modify Your Sedentary Habits: Utilize wearable fitness trackers or smartphone apps to gain awareness of your daily sitting hours. Set realistic goals to progressively reduce this time.

- Embrace Active Household Chores: Activities like vacuuming, mopping, vigorous cleaning, or even enthusiastic cooking contribute valuable MET-hours and promote a healthier home environment.

- Active Commuting: If feasible, walk or cycle for part or all of your commute. If using public transport, get off a stop earlier and walk the rest of the way.

- Socialize Actively: Suggest walks, hikes, or active outings instead of always meeting friends for sedentary activities like coffee or meals.

The BioBrain Bottom Line: Move More, Sit Less, Age Better

The scientific verdict is clear: a chronically sedentary lifestyle is a potent catalyst for accelerated biological aging, operating insidiously at the cellular level. While structured exercise remains a cornerstone of good health, it’s not a panacea for the harms of excessive, unbroken sitting time. The most effective defense involves a two-pronged approach: maintain regular exercise AND diligently minimize overall sitting while purposefully incorporating frequent movement breaks throughout your day. These conscious efforts are critical for supporting robust cellular health, potentially decelerating aspects of genetic aging, and significantly enhancing not just your lifespan, but your healthspan – the years you live in good health and full function. Take an honest look at your daily routine: are you actively and consistently breaking free from the chair? Your future, more vibrant self will profoundly thank you.

Frequently Asked Questions (Q&A)

Q1: How much sitting is considered too much for my health?

Q2: Can I reverse the aging effects of a previously sedentary lifestyle?

Q3: What are the most effective ways to break up long periods of sitting, especially with a desk job?

Q4: Does standing all day instead of sitting avoid these negative effects?

Q5: How does sitting specifically impact my telomeres and DNA?

Disclaimer

The information provided on BioBrain is intended for educational purposes only and is grounded in science, common sense, and evidence-based medicine. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider before making significant changes to your diet, exercise routine, or overall health plan.

References

- KING, ABBY C., POWELL, KENNETH E., & KRAUS, WILLIAM E. (2019) "The US Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report—Introduction"

- KRAUS, WILLIAM E., JANZ, KATHLEEN F., POWELL, KENNETH E., et al. (2019) "Daily Step Counts for Measuring Physical Activity Exposure and Its Relation to Health"

- JAKICIC, JOHN M., KRAUS, WILLIAM E., POWELL, KENNETH E., et al. (2019) "Association between Bout Duration of Physical Activity and Health: Systematic Review"

- KATZMARZYK, PETER T., POWELL, KENNETH E., JAKICIC, JOHN M., et al. (2019) "Sedentary Behavior and Health: Update from the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee"

- ERICKSON, KIRK I., HILLMAN, CHARLES, STILLMAN, CHELSEA M., et al. (2019) "Physical Activity, Cognition, and Brain Outcomes: A Review of the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines"

- MCTIERNAN, ANNE, FRIEDENREICH, CHRISTINE M., KATZMARZYK, PETER T., et al. (2019) "Physical Activity in Cancer Prevention and Survival: A Systematic Review"

- BOWDEN DAVIES, KELLY A., SPRUNG, VICTORIA S., NORMAN, JULIETTE A., et al. (2019) "Physical Activity and Sedentary Time: Association with Metabolic Health and Liver Fat"

- Ekelund, U., Tarp, J., Steene-Johannessen, J., et al. (2019) "Dose-response associations between accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary time and all-cause mortality: systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis"

- Healy, G. N., Dunstan, D. W., Salmon, J., et al. (2008) "Breaks in sedentary time: beneficial associations with metabolic risk"

- World Health Organization (2020) "WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour"

- American Heart Association "Recommendations for Physical Activity in Adults and Kids"

- Compendium of Physical Activities "Compendium of Physical Activities Website"

Tags :

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Biological aging

- Sitting risks

- Longevity strategies

- Cellular aging mechanisms

- Telomere shortening

- Mets explained

- Health impact of inactivity

- Evidence based health advice

- Genetic aging factors

- Combat premature aging

- Benefits of breaking up sitting

- How to reduce cellular aging from sitting

- Dangers of prolonged sitting even with exercise