Soy Unveiled: Debunking Myths with Science and Uncovering Health Realities

- Olivia Hart

- Nutrition , Food science , Health , Evidence based medicine

- May 11, 2025

Table of Contents

Fast Facts: Soy at a Glance

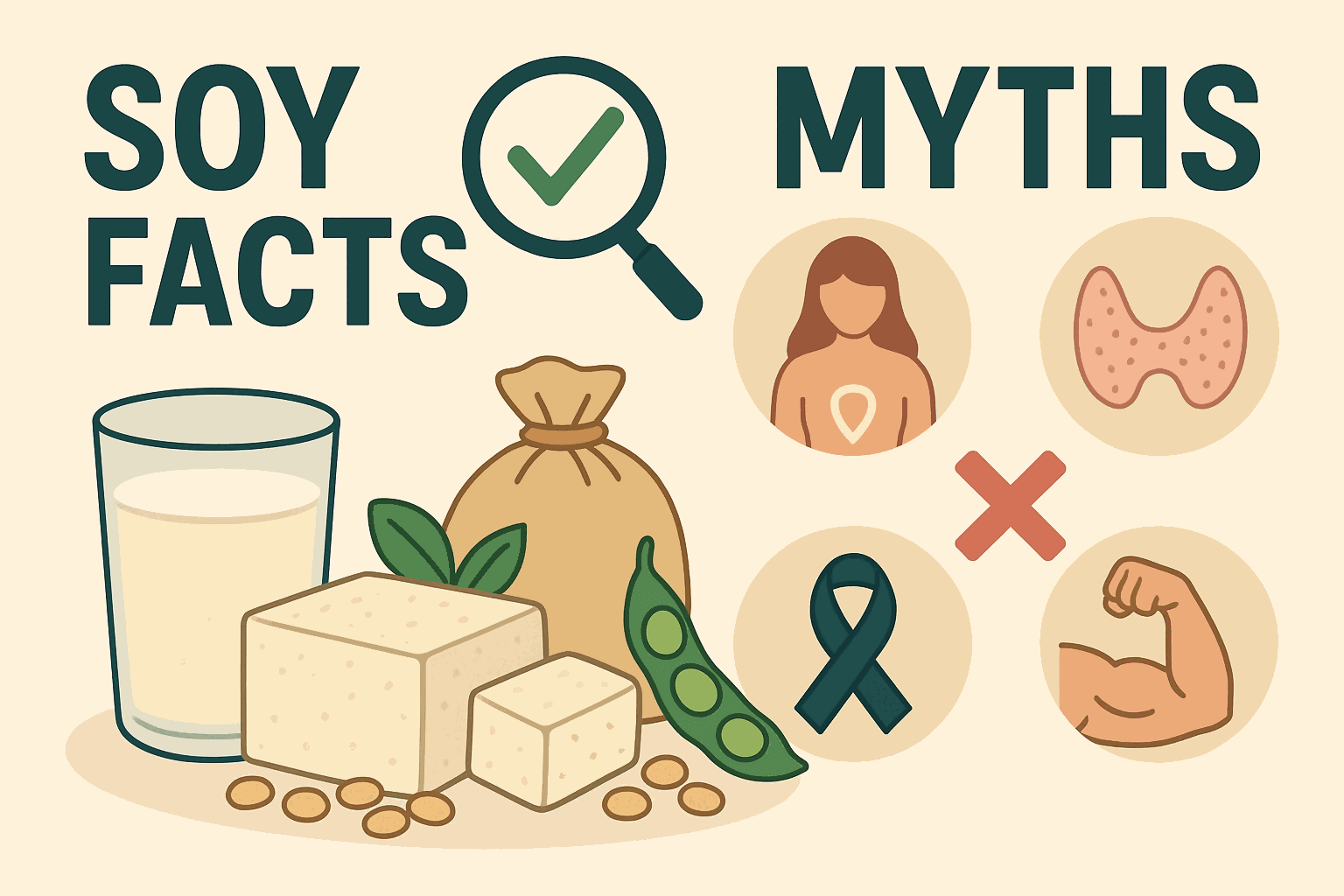

- Men’s Health: Scientific consensus shows soy does not negatively impact testosterone or “feminize” men when consumed in normal dietary amounts. Concerns arise from extreme, unrealistic intake levels.

- Thyroid Function: Soy is generally safe for the thyroid in individuals with adequate iodine intake. However, it can affect the absorption of thyroid medication, so timing is key for those on treatment.

- Breast Cancer: Lifelong, moderate soy consumption, particularly common in Asian diets, is linked to a lower risk of breast cancer. For survivors, it may even reduce recurrence.

- Nutritional Powerhouse: Soy is a complete protein, rich in omega fatty acids, vitamins (like B vitamins), and minerals (magnesium, iron, calcium).

- Functional Food: Soy offers health benefits beyond basic nutrition, supporting overall wellness as part of a balanced diet.

Demystifying Soy: Addressing Common Concerns

Soy has long been a staple in many traditional diets, especially in East Asia, where populations boast impressive longevity. Yet, in many Western cultures, soy is often viewed with suspicion, becoming the subject of heated debate and misinformation. Accusations range from disrupting hormonal balance to increasing cancer risk. But what does the science actually say in 2025? Let’s delve into evidence-based medicine and common sense to unravel the truth about soy. The controversy surrounding soy often stems from its content of isoflavones, which are compounds classified as phytoestrogens (plant-based estrogens). Because they can bind to estrogen receptors in the body, concerns have been raised about their potential effects. However, it’s crucial to understand that phytoestrogens are not the same as human estrogen and their action is far more complex and often beneficial.

Myth 1: Soy “Feminizes” Men and Destroys Testosterone

The Claim: Soy’s phytoestrogens will lower testosterone, reduce sperm quality, and lead to feminizing effects in men.

The Scientific Reality: This is one of the most pervasive myths about soy.

- Different Action: Isoflavones are selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs). This means they can have weak estrogenic or even anti-estrogenic effects depending on the tissue and the body’s own estrogen levels. They do not simply mimic strong human estrogen.

- Robust Evidence: Numerous meta-analyses of clinical studies have overwhelmingly concluded that soy food consumption, or isoflavone intake at levels consistent with typical dietary consumption (even high-soy Asian diets), does not adversely affect testosterone levels, sperm parameters, or induce feminizing effects in men. A significant meta-analysis published in Fertility and Sterility examined 15 placebo-controlled studies and more than 30 other reports, finding no significant effects of soy protein or isoflavone intake on reproductive hormones in men [1, 2].

- The “Extreme Dose” Confusion: Concerns often arise from isolated case reports involving individuals consuming extraordinarily high, unrealistic amounts of soy (e.g., reports of men drinking gallons of soy milk daily, far exceeding any typical dietary pattern) or from animal studies using very high doses of isolated isoflavones, which are not directly applicable to human dietary intake [3]. The original article’s mention of “extractive isoflavones” not being recommended for men might refer to highly concentrated supplements taken without medical guidance, which differs significantly from whole soy food consumption. For dietary soy, the evidence supports its safety.

The Bottom Line: For men consuming soy as part of a balanced diet (tofu, tempeh, edamame, soy milk), there’s no scientific basis for fears of feminization or hormonal disruption.

Myth 2: Soy Is Harmful to the Thyroid Gland

The Claim: Soy consumption can impair thyroid function and lead to hypothyroidism.

The Scientific Reality: The relationship between soy and thyroid health is nuanced but generally reassuring for most people.

- Goitrogens: Soy contains compounds called goitrogens, which can interfere with thyroid hormone synthesis. This is true for many healthy foods, including cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, kale, etc.).

- Iodine is Key: The potential goitrogenic effect of soy is primarily a concern in individuals with iodine deficiency [4]. The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes the importance of adequate iodine intake for thyroid health. When iodine intake is sufficient, studies show that soy consumption does not typically disrupt thyroid function in healthy individuals [5, 6].

- Medication Interaction: For individuals with pre-existing hypothyroidism who are taking levothyroxine (thyroid hormone replacement medication), soy products can interfere with the absorption of the medication [7]. This doesn’t mean soy must be entirely avoided, but rather that the medication should not be taken at the same time as soy foods. It’s generally recommended to wait at least 4 hours between consuming soy and taking levothyroxine [8]. Consulting with a healthcare provider for personalized advice is crucial for these individuals.

The Bottom Line: If your iodine intake is adequate and you don’t have a pre-existing thyroid condition, soy is unlikely to harm your thyroid. If you take thyroid medication, discuss soy consumption and medication timing with your doctor.

Myth 3: Soy Increases the Risk of Breast Cancer

The Claim: The phytoestrogens in soy can stimulate breast cancer growth.

The Scientific Reality: This is perhaps the most misunderstood area. Current research, particularly from human studies, points in the opposite direction for dietary soy.

- Early Life Exposure: Epidemiological studies in Asian populations, where soy is consumed regularly from a young age, show a correlation with a lower risk of developing breast cancer later in life [9, 10]. This suggests that lifelong, moderate consumption may offer protective benefits.

- Survivors’ Benefit: Importantly, for breast cancer survivors, soy consumption has been associated with a reduced risk of recurrence and mortality. A meta-analysis of studies involving over 9,500 breast cancer survivors found that soy intake was associated with a significant reduction in both recurrence and overall mortality [11]. Another comprehensive review supports the safety and potential benefits of soy consumption for breast cancer survivors [12].

- Estrogen Receptor Modulation: The isoflavones in soy (like genistein and daidzein) can bind to estrogen receptors. However, they preferentially bind to estrogen receptor beta ($ER\beta$) rather than estrogen receptor alpha ($ER\alpha$). Activation of $ER\beta$ is often associated with anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic (cell death) effects in cancer cells, while $ER\alpha$ activation is more commonly linked to cancer promotion [13]. This differential binding may explain some of soy’s protective effects.

- Official Stances: Major health organizations, including the American Cancer Society and the World Cancer Research Fund, state that consuming moderate amounts of soy foods is safe for everyone, including breast cancer survivors [14, 15]. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has also confirmed the safety of isoflavones for postmenopausal women, who are generally at higher risk for breast cancer [16].

The Bottom Line: Far from increasing risk, moderate consumption of whole soy foods appears safe and may even be protective against breast cancer, especially when introduced early in life, and beneficial for survivors. Concerns about isolated, high-dose isoflavone supplements are different from dietary soy.

The Undeniable Nutritional Value of Soy

Beyond debunking myths, it’s essential to recognize soy’s impressive nutritional profile and its role as a functional food.

- Record-Holder for Protein: Soybeans are unique among legumes for their high protein content, which can be up to 40% of their dry weight. Crucially, soy protein is a complete protein, meaning it contains all nine essential amino acids that the human body cannot synthesize on its own. This makes it an excellent plant-based alternative to animal protein [17].

- Rich in Healthy Fats: Soybeans contain beneficial unsaturated fats, including omega-6 (linoleic acid) and omega-3 (alpha-linolenic acid) fatty acids, which are important for heart and brain health [17].

- Micronutrient Power: Soy is a good source of various vitamins and minerals, including:

- B Vitamins: Essential for energy metabolism and nerve function.

- Iron: Crucial for oxygen transport (though non-heme iron, absorption is enhanced with vitamin C).

- Magnesium: Involved in over 300 biochemical reactions in the body.

- Calcium: Important for bone health (especially in fortified soy products like soy milk and tofu made with calcium sulfate).

- Fiber Content: Whole soybeans and less processed soy foods like edamame and tempeh are good sources of dietary fiber, promoting digestive health and satiety.

- Isoflavones as Antioxidants: Beyond their phytoestrogenic activity, isoflavones also possess antioxidant properties, helping to combat oxidative stress in the body, which is implicated in chronic diseases [13].

Soy: A True Functional Food

The term “functional food” refers to foods that offer health benefits beyond basic nutrition. Soy squarely fits this description [17]. Its unique combination of high-quality protein, healthy fats, micronutrients, and bioactive compounds like isoflavones contributes to various health advantages:

- Heart Health: Studies suggest soy consumption can improve cholesterol levels (lowering LDL or “bad” cholesterol) and may have other cardiovascular benefits [18, 19].

- Menopausal Symptom Relief: Soy isoflavones may help reduce the frequency and severity of hot flashes in some menopausal women, although effects can vary [20].

- Bone Health: Some research indicates that soy isoflavones may contribute to maintaining bone density, particularly in postmenopausal women, though more research is needed [21].

Incorporating Soy into Your Diet: There are many ways to enjoy soy:

- Tofu: Versatile and can be grilled, baked, stir-fried, or blended.

- Tempeh: Fermented soybean cake with a nutty flavor and firm texture. Fermentation can also increase the bioavailability of some nutrients and add probiotics.

- Edamame: Young, green soybeans, often steamed or boiled and served in the pod.

- Soy Milk: A popular dairy milk alternative, often fortified with calcium and vitamin D.

- Miso: Fermented soybean paste used in Japanese cuisine, rich in probiotics.

- Natto: Fermented whole soybeans with a very strong flavor and sticky texture, exceptionally rich in vitamin K2.

Conclusion: Embrace Soy with Confidence (and Common Sense)

The weight of scientific evidence in 2025 indicates that soy, when consumed as whole or minimally processed foods as part of a balanced diet, is not only safe but also offers significant health benefits. The myths surrounding soy often arise from misinterpretations of animal studies, isolated compound research, or anecdotal reports of extreme consumption patterns.

For most individuals, incorporating diverse soy foods into their meals is a healthy choice that can contribute valuable protein, essential fats, and beneficial phytonutrients. As with any food, moderation and variety are key. If you have specific health conditions, particularly thyroid issues requiring medication, or a history of estrogen-sensitive cancers, it’s always wise to discuss your dietary choices with your healthcare provider or a registered dietitian.

Ultimately, science supports soy as a valuable component of a healthy living protocol. Don’t let outdated myths prevent you from enjoying this nutritious and versatile food.

Disclaimer

The information provided on BioBrain is intended for educational purposes only and is grounded in science, common sense, and evidence-based medicine. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider before making significant changes to your diet, exercise routine, or overall health plan.

References

- Hamilton-Reeves, J. M., Vazquez, G., Duval, S. J., Phipps, W. R., Kurzer, M. S., & Messina, M. J. (2010) "Clinical studies show no effects of soy protein or isoflavones on reproductive hormones in men: results of a meta-analysis"

- Reed, K. E., Camargo, J., Hamilton-Reeves, J., Kurzer, M., & Messina, M. (2021) "Neither soy nor isoflavone intake affects male reproductive hormones: An expanded and updated meta-analysis of clinical studies"

- Martinez, J., & Lewi, J. E. (2008) "An unusual case of gynecomastia associated with soy product consumption"

- Messina, M., & Redmond, G. (2006) "Effects of soy protein and soybean isoflavones on thyroid function in healthy adults and hypothyroid patients: a review of the relevant literature"

- Otun, J., Sahebkar, A., Östlundh, L., Atkin, S. L., & Sathyapalan, T. (2019) "Systematic Review and Meta-analysis on the Effect of Soy on Thyroid Function"

- Sathyapalan, T., Manuchehri, A. M., Thatcher, N. J., Rigby, A. S., Chapman, T., Kilpatrick, E. S., & Atkin, S. L. (2011) "The effect of soy phytoestrogen supplementation on thyroid status and cardiovascular risk markers in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study"

- Bell, D. S., & Ovalle, F. (2001) "Use of soy protein supplement and resultant need for increased dose of levothyroxine"

- Liel, Y., Harman-Boehm, I., & Shany, S. (1996) "Evidence for a clinically important adverse interaction between levothyroxine and soy bean products"

- Wu, A. H., Ziegler, R. G., Horn-Ross, P. L., Nomura, A. M., West, D. W., Kolonel, L. N., Hoover, R. N., & Pike, M. C. (1996) "Tofu and risk of breast cancer in Asian-Americans"

- Shu, X. O., Jin, F., Dai, Q., Wen, W., Potter, J. D., Kushi, L. H., Ruan, Z., Gao, Y. T., & Zheng, W. (2002) "Adolescent and adult soy intake and risk of breast cancer in Asian-Americans"

- Chi, F., Wu, R., Zeng, Y. C., Xing, R., Liu, Y., & Xu, Z. G. (2013) "Post-diagnosis soy food intake and breast cancer survival: a meta-analysis of cohort studies"

- Messina, M. J., & Loprinzi, C. L. (2001) "Soy for breast cancer survivors: a critical review of the literature"

- Messina, M. (2016) "Impact of Soy Foods on the Development of Breast Cancer and the Prognosis of Breast Cancer Patients"

- Kulling, S. E., & Watzl, B. (2003) "Phytoestrogens: a review of the current literature on their role in health"

- Wang, H., & Murphy, P. A. (1994) "Isoflavone Content in Commercial Soybean Foods"

- Bhat, H. K., & Pezzuto, J. M. (2002) "Cancer chemoprevention: a practical approach"

- Setchell, K. D., & Cassidy, A. (1999) "Dietary isoflavones: biological effects and relevance to human health"

- American Cancer Society (2023) "Soy and Cancer Risk: Our Expert's Advice"

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (2023) "Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: a Global Perspective"

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS) (2015) "Scientific opinion on the risk assessment for peri- and post-menopausal women taking food supplements containing isolated isoflavones"

- Messina, M. (1999) "Legumes and soybeans: overview of their nutritional profiles and health effects"

- Jenkins, D. J., Mirrahimi, A., Srichaikul, K., Berryman, C. E., Wang, L., Carleton, A., ... & Kris-Etherton, P. (2010) "Soy protein reduces serum cholesterol by both intrinsic and food displacement mechanisms"

- Anderson, J. W., Johnstone, B. M., & Cook-Newell, M. E. (1995) "Meta-analysis of the effects of soy protein intake on serum lipids"

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (1999) "Food Labeling: Health Claims; Soy Protein and Coronary Heart Disease"

- Taku, K., Melby, M. K., Kronenberg, F., Kurzer, M. S., & Messina, M. (2012) "Extracted or synthesized soybean isoflavones reduce menopausal hot flash frequency and severity: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials"

- Ma, D. F., Qin, L. Q., Wang, P. Y., & Katoh, R. (2008) "Soy isoflavone intake increases bone mineral density in the spine of menopausal women: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials"

- Pawłowska, K. A., Krawczeniuk, A., Gajewska, M., & Stochmal, A. (2022) "The Role of Soy Isoflavones in the Prevention of Bone Loss in Postmenopausal Women: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials"

Tags :

- Soy

- Phytoestrogens

- Isoflavones

- Soy health benefits

- Soy myths

- Hormonal health

- Thyroid function

- Cancer prevention

- Plant based protein

- Functional foods

- Nutrition science