The Physiological Sigh: A Science-Backed Tool for Rapid Stress Regulation

- Olivia Hart

- Health , Well being , Stress management , Neuroscience

- May 7, 2025

Table of Contents

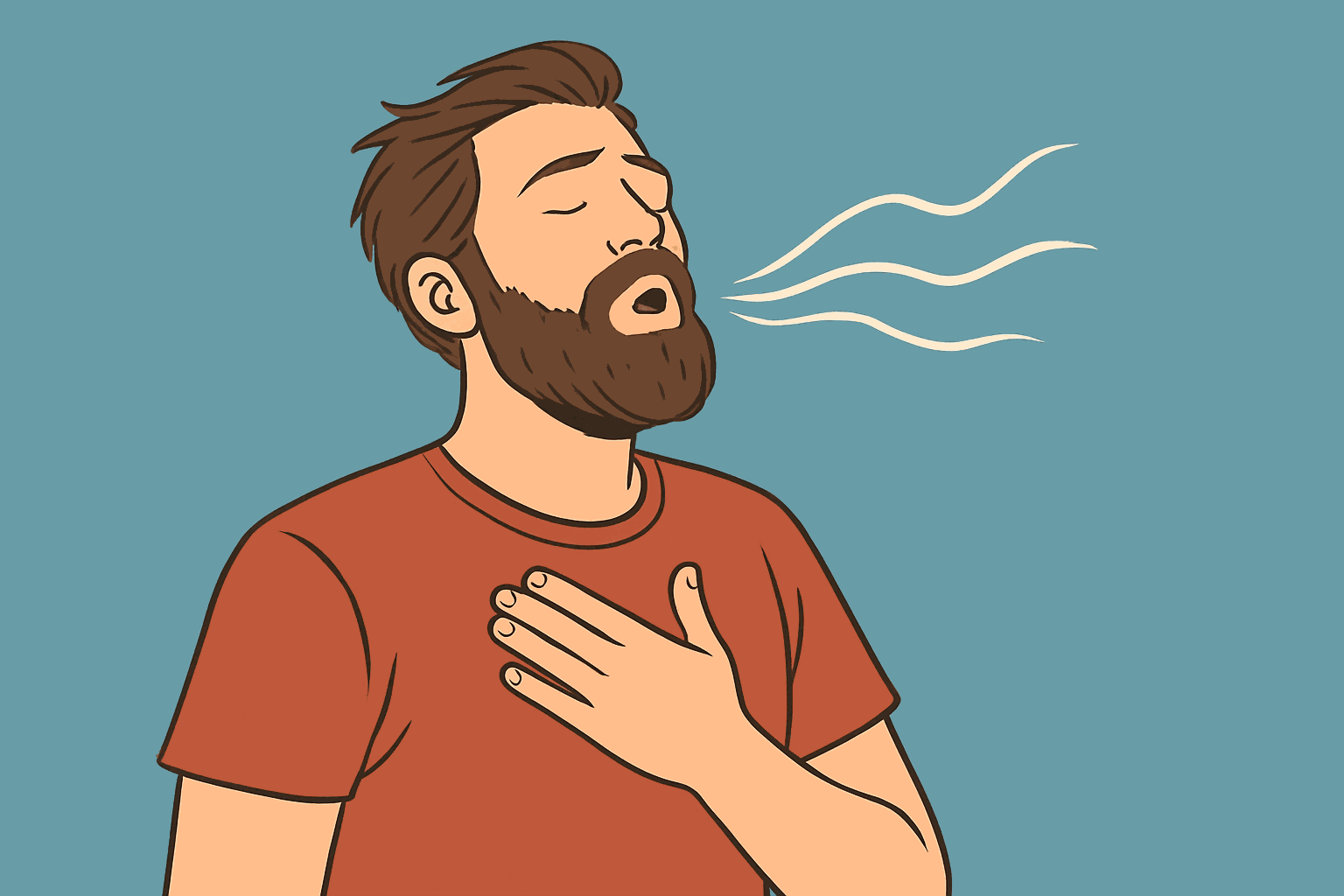

In our fast-paced lives, stress can often feel like an unwelcome constant. While complex solutions abound, sometimes the most effective tools are the simplest and most innate. Enter the physiological sigh, a remarkably efficient breathing technique grounded in robust science, offering a quick and accessible way to manage stress and anxiety in real-time. This isn’t just about taking a “deep breath”; it’s a specific respiratory pattern that your body naturally uses, and that you can consciously harness for immediate calm.

What is the Physiological Sigh?

The physiological sigh involves a distinct breathing pattern: two sharp inhalations through the nose followed by a long, slow exhalation through the mouth.

- The first inhale is typically deep.

- The second inhale is shorter and quicker, designed to further inflate the lungs.

- The exhale is prolonged and controlled.

This pattern isn’t a new invention; it’s an unconscious reflex first identified by scientists in the 1930s [8, 9]. We spontaneously perform physiological sighs approximately every five minutes, even during sleep, to maintain healthy lung function. However, its power as a conscious tool for stress regulation has been brought to the forefront by neuroscientists like Dr. Andrew Huberman of Stanford University, whose research highlights its rapid calming effects [2, 10].

The Science Behind the Sigh: How Does It Work?

The effectiveness of the physiological sigh lies in its direct impact on our respiratory and nervous systems. It’s a beautiful example of how conscious control of an autonomic process can powerfully influence our physiological and psychological state.

1. Maximizing Lung Inflation and Reopening Alveoli

Our lungs contain millions of tiny air sacs called alveoli, where the crucial exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide takes place. Due to shallow breathing, especially during stress, some of these alveoli can collapse (a state known as atelectasis).

The double inhalation of the physiological sigh is uniquely effective because it creates maximal inflation of the lungs. The second, smaller inhale on top of the first full one helps to pop open these collapsed alveoli, significantly increasing the surface area available for gas exchange [1, 7, 9]. Think of it as fully inflating a balloon that had partially deflated.

2. Optimizing Carbon Dioxide Exchange

When alveoli are reinflated, the efficiency of gas exchange improves. This means more oxygen can enter the bloodstream, and, critically, more carbon dioxide (CO2) can be expelled during the prolonged exhalation [6, 7].

An accumulation of CO2 in the bloodstream can contribute to feelings of anxiety and panic. By efficiently offloading CO2, the physiological sigh helps to regulate blood pH and promote a state of calm.

3. Activating the Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS)

Our autonomic nervous system has two main branches: the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), responsible for the “fight or flight” stress response, and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), which governs the “rest and digest” state of calm and recovery.

The long, slow exhale of the physiological sigh is key to shifting the balance from the SNS to the PNS [2, 5]. This is largely mediated by the vagus nerve, the main component of the PNS. Slowing down the exhalation stimulates the vagus nerve, which in turn sends signals to the brain to slow heart rate, reduce blood pressure, and promote relaxation [3, 4]. This is why you often feel an almost immediate sense of relief.

4. The Neural Basis of Sighing

Research by neurobiologists like Dr. Jack Feldman and Dr. Mark Krasnow has pinpointed the specific neural circuits in the brainstem responsible for generating sighs [8, 9]. They discovered a small group of neurons that control this vital reflex, underscoring its fundamental role in our physiology. While these sighs are often involuntary, the beauty of the physiological sigh is our ability to consciously trigger this beneficial mechanism.

Evidence-Based Benefits of the Physiological Sigh

The calming effects of the physiological sigh aren’t just anecdotal; they are supported by scientific research.

- Rapid Stress and Anxiety Reduction: This is perhaps the most notable benefit. The physiological sigh can provide an immediate, “in-the-moment” reduction in stress and feelings of anxiety [2, 10]. Unlike some stress-relief techniques that require prolonged practice, even one to three physiological sighs can make a difference.

- Improved Mood and Well-being: A study published in Cell Reports Medicine by Balban et al. (from Stanford, involving Dr. Huberman and Dr. David Spiegel) found that daily 5-minute sessions of cyclic sighing (another term for physiological sighs) improved mood and reduced physiological arousal more effectively than mindfulness meditation and other breathing techniques like box breathing or cyclic hyperventilation over a one-month period [10, 11].

- Reduced Physiological Arousal: The same study demonstrated that cyclic sighing led to a significant reduction in resting respiratory rate, an indicator of increased calmness [10, 11]. Other markers like heart rate and heart rate variability (HRV) can also be positively influenced.

- Enhanced Respiratory Function: By regularly ensuring full lung inflation and preventing alveolar collapse, this technique supports overall lung health and efficiency [1, 9].

- Improved Focus and Mental Clarity: By calming the nervous system and reducing the “noise” of stress, the physiological sigh can help improve focus and cognitive function [2].

How to Perform the Physiological Sigh: A Practical Guide

Harnessing the power of the physiological sigh is simple. Here’s how:

- Posture: You can be sitting up or lying down. If sitting, try to sit upright to allow your lungs to fully expand.

- Inhalation (Double):

- Take a deep inhale through your nose, filling your lungs comfortably.

- Without exhaling, take another short, sharp inhale through your nose, “sneaking in” a bit more air to maximally inflate your lungs.

- Exhalation (Extended):

- Exhale slowly and fully through your mouth, making the exhale noticeably longer than the total duration of the two inhales. Let all the air out.

- Repetitions:

- For immediate relief from acute stress, 1 to 3 physiological sighs are often sufficient.

- For sustained benefits in mood and stress resilience, practice for about 5 minutes daily, as suggested by the research [10, 11].

When to Use It:

- Before a stressful meeting or presentation.

- During an exam or when facing a mental block.

- When you feel overwhelmed or anxious.

- During emotional arguments to regain composure.

- Proactively throughout the day as a “reset” button.

Why It’s More Than Just a “Deep Breath”

While any form of deep breathing can be beneficial, the physiological sigh’s specific structure—the double inhale followed by an extended exhale—offers distinct advantages:

- Maximal Alveolar Recruitment: The second inhale ensures a more complete inflation of the lungs than a single deep breath might achieve [1, 9].

- Efficient

CO2Offloading: The combination of full inflation and extended exhalation is particularly effective at balancing gas levels [6, 7]. - Rapid PNS Activation: The deliberate extended exhale is a powerful trigger for the parasympathetic response [2, 3, 4].

The Stanford study indeed showed that the exhale-focused cyclic sighing provided more significant improvements in mood compared to other breathing exercises tested [10, 11].

Conclusion: Your Built-In Tool for Calm

The physiological sigh is a testament to the profound connection between our breath and our brain. It’s a simple, no-cost, evidence-based tool that empowers you to take control of your stress response in mere moments. Grounded in our innate physiology and validated by modern neuroscience, incorporating this technique into your daily routine can be a powerful step towards greater calm, improved well-being, and enhanced resilience in the face of life’s challenges.

Give it a try—your nervous system will thank you.

References

- Oku, Y., et al. (2019). Interaction between sighs and sustained inflation breaths in regulating atelectasis in anesthetized rats. Journal of Applied Physiology, 126(6), 1677-1685. (https://journals.physiology.org/doi/10.1152/japplphysiol.00050.2019)

- Huberman Lab. (n.d.). Breathwork Protocols for Health, Focus & Stress. (https://www.hubermanlab.com/newsletter/breathwork-protocols-for-health-focus-stress)

- Vlemincx, E., et al. (2019). The Power of the Sigh: A Neurobiological and Clinical Review. Neuron, 103(2), P185-198. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31225967/

- Charlie Health. (2024, January 5). Vagus Nerve Exercises. (https://www.charliehealth.com/post/vagus-nerve-exercises)

- BetterUp. (2023, July 26). 10 Parasympathetic Breathing Exercises for Sleep, Stress & Relaxation. (https://www.betterup.com/blog/parasympathetic-breathing-exercises)

- Government Science and Engineering. (2021, November 26). Is a Sigh Just a Sigh? (https://governmentscienceandengineering.blog.gov.uk/2021/11/26/is-a-sigh-just-a-sigh/)

- Systers. (n.d.). The Physiological Sigh. (https://www.systers.bio/en/magazin-systers/the-physiological-sigh/)

- UCLA Newsroom. (2016, February 8). UCLA and Stanford researchers pinpoint origin of sighing reflex in the brain. (https://newsroom.ucla.edu/releases/ucla-and-stanford-researchers-pinpoint-origin-of-sighing-reflex-in-the-brain)

- Li, P., Janczewski, W. A., Yackle, K., Kam, K., Pagliardini, S., Krasnow, M. A., & Feldman, J. L. (2016). The peptidergic control circuit for sighing. Nature, 530(7590), 293-297. (This is the primary research from Feldman/Krasnow labs often referenced by sources like UCLA Newsroom).

- Balban, M. Y., Neri, E., Kogon, M. M., Weed, L., Nouriani, B., Jo, B., Holl, G., Zeitzer, J. M., Spiegel, D., & Huberman, A. D. (2023). Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal. Cell Reports Medicine, 4(1), 100895. (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100895)

- Stanford Medicine SCOPE. (2023, February 9). ‘Cyclic sighing’ can help breathe away anxiety. (https://scopeblog.stanford.edu/2023/02/09/cyclic-sighing-can-help-breathe-away-anxiety/)

- Oura Ring Blog. (2024, February 23). Physiological Sigh: A 30-Second Breathing Exercise to Lower Stress. (https://ouraring.com/blog/what-is-the-physiological-sigh-how-to-do-it/)

Disclaimer

The information provided on BioBrain is intended for educational purposes only and is grounded in science, common sense, and evidence-based medicine. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider before making significant changes to your diet, exercise routine, or overall health plan.

Tags :

- Physiological sigh

- Breathing technique

- Stress regulation

- Anxiety relief

- Parasympathetic nervous system

- Vagus nerve

- Andrew huberman

- Evidence based medicine

- Lung function

- Co2 exchange

- Stress relief